This post details how to grow amazing okra (abelmoschus esculentus), even if you did not grow up in the south. Have no fear; it is easy!

My Okra Introduction

I will admit that, as a former Midwesterner, I did not grow up with okra. Other than eating small nibbles of it encased in fried batter at a restaurant once, the green vegetable and I had not made acquaintance. When I moved to the South, Mr. Grump introduced me to the vegetable in all its slimy glory, boiled with a bit of salt sprinkled on top. Somehow, the visual of what appeared to be snot draining off of these pods did not deter me from trying it. I was surprised that I found its flavor pleasing. This was a fortunate discovery, as local Florida gardeners quickly warned me that many vegetables commonly grown in other parts of the country will sprout and quickly shrivel in our summer heat.

Using the Square Foot Method to Grow Okra

The first summer here, I had Mr. Grump make me several square foot gardens for the porch. These were made simply, by cutting two 8-foot long 2″x8″ boards in half and fastening them together with screws. We then filled these square boxes with the formula recommended in the Square Foot Gardening book: 1/3 compost (we used mushroom compost), 1/3 peat moss, and 1/3 vermiculite. Well, we thought we did. We later learned that the vermiculite available at most big box stores is fine rather than the coarse type which was recommended. It was not until later that we stumbled upon some coarse vermiculite at a local nursery that we even realized our mistake.

We had no clue what we were doing and rarely watered the garden. The plants only had about 6″ of dirt in which to grow roots. Despite this, the Clemson Spineless okra that we planted grew tall and gave an abundant harvest. We saved seeds for the next year, and after a few seasons, our Clemson Spineless okras seem to produce more than before. These okra are consistently tender and have the benefit of being spineless. This simply means that they don’t stab you in the hand/face when you pick them. Below see an average leaf, approximately 9″ across.

Alabama Red Okra

Despite these good qualities, last season I wanted some variety in my slimy green vegetables. I ordered Alabama Red seeds from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds to plant in addition to the saved seeds of the Clemson Spineless. These seeds were planted in the same conditions as before, a 4′ x 4′ bed with approximately 7″ of our modified Mel’s mix.

Let me tell you, the Alabama Red plants certainly were impressive. The stalks grew thicker and taller than any of our previous Clemsons. The leaves averaged at a massive 14″ across. They produced pods even more prolifically, and the pods remained tender despite being significantly more plump than the Clemson Spineless. Aesthetically, the red-veined leaves and red-tinted pods were quite pleasing to the eye. An additional potential benefit of the Alabama Red is that it is unlikely that the police would confuse them with marijuana if they ever stopped by our property due to their leaves having thicker lobes than the Clemsons. Yes, this apparently happened to a poor gardener in Georgia.

Given my enthusiasm for these beautiful and prolific plants, what more could I want in an okra? Well, you may notice one word is missing from the title “Alabama Red,” and that word is “spineless.” You see, every time I went to the garden to harvest these vegetables (which was almost daily, due to the number of pods produced per plant), I would inevitably be stabbed multiple times. Then, when I would pick them up to chop them for use in a recipe, I would be stabbed again.

Pollination and Seed Saving

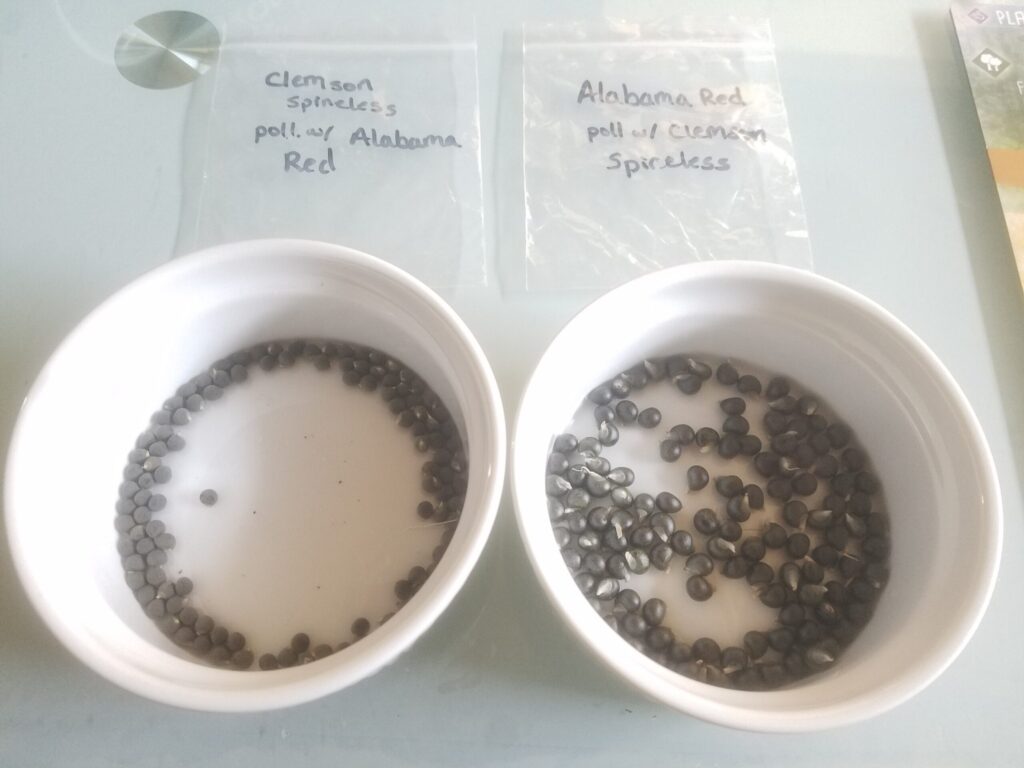

As I prefer not to be maimed by my produce, I decided to engage in a bit of self-pollination in attempt to make an okra cross that was beautiful, large, AND spineless. In hopes of increasing my odds, I cross-pollinated some Clemson Spineless flowers with Alabama Red pollen. I also cross-pollinated some Alabama Red flowers with Clemson Spineless pollen. I tracked these crosses with a high-tech system (i.e., putting colored twisty ties around the corresponding stems/pods). The experiment almost failed on a couple of occasions due to my enthusiasm for harvesting, which led me very close to absentmindedly picking and using these experimental pods for dinner rather than seeds. However, I managed to reign in my harvesting impulse and have successfully dried and saved several seeds from each cross attempt.

Be watching next year for an update regarding the successfulness (or lack thereof) of this experiment. Will any produce large, beautiful, and non-stabby okras? Or will they all be the worst of both worlds, being small, boring, and stabby? Next year’s summer garden will tell!

Bonus: if you have been growing okra and want to save your own seeds for next year, wait to harvest until the pods are somewhat dry and cracking (see photo below). The seeds should be plump and back. If they are still white or grey, they are not yet ready.

That’s it! Growing amazing okra at home is easy. If you’re looking for another easy southern crop, I recommend checking out this post on growing jewels of opar. What are your favorite heat-resistant crops? Feel free to post below!